label.skip.main.content

My Life

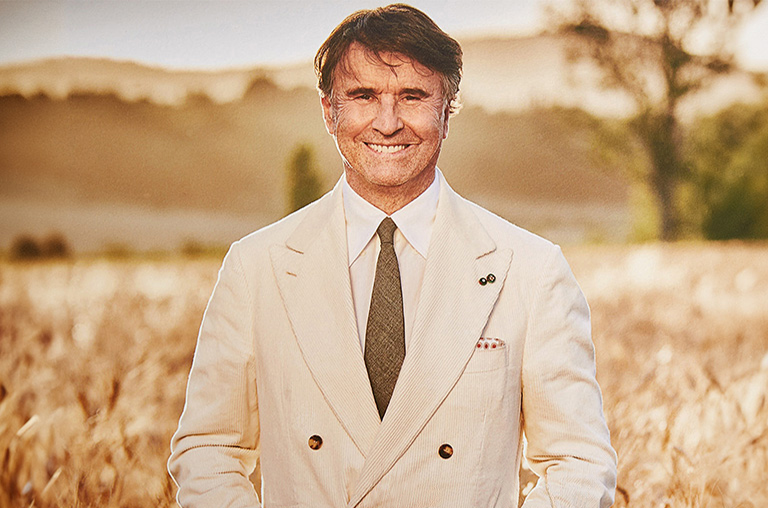

Brunello Cucinelli, photo by Benjamin McMahon

My Youth

‘I can still perceive, in the senses, the scent, sounds and lights of the farming life I was born into. We were a family of thirteen, we lived in the countryside in Castel Rigone, in a rustic farmhouse surrounded by fields, fruit orchards and the woods. That life was like a small world, because it had in it the seed of every fundamental thing in life.

Brunello, second from the left, with his brothers and a cousin, at home in the countryside in Castel Rigone

We were sharecroppers, so a vital moment for us was when, at the end of the year, around Christmas time, we used to go to the landlord, meaning the farm owner, to do accounts. My grandfather Fiorino and my uncle Tonino were in charge of this task. When they were away, those of us who stayed home, waiting for them to meet the landlord, used to reflect on how things had gone, if the harvest had been plentiful: wheat was good, the olives not as good… what would the landlord say? When my uncle and my grandfather came home, they never talked numbers. All they said was, “It went pretty well, it was a good year, let’s hope next year will be better”. This meant there was little money. But I didn’t mind this moderation. Wheat was more or less life itself for us farmers: the value of the land was measured based on the amount of wheat harvested. I loved seeing my family satisfied with the harvest. We gave the first bale of wheat to the community, at the behest of my grandfather. That’s when I first learned the great theme in life: the balance between profit and giving back.

1- A 16-year-old Brunello, studying as a building surveyor

2- Brunello in 2008 with one of his innovations: the gray tuxedo

At the time, farmers could avail themselves of only few means, there was no electricity and the major labor forces were animals and people. That is why everybody had their own task, and I loved the fact that there was always a correspondence between the person who was given a task and the task itself, meaning that each person was perfectly suited for the task, an old farming rule. My father, who was the strongest, carried out the most physically demanding tasks, one of my uncles, instead, who was slightly weaker, was in charge of managing the animals, so to each his own task. I was a skinny boy, and as such my grandfather and my uncle used to call me “little fox”, so I was responsible for picking olives, because I could climb up to the highest branches without breaking them thanks to my light weight. I was also very accurate, so I earned myself my second task, which was to guide the ox-drawn plow. There were two of us: my dad, who guided the plow, and me, in front of it, making sure that the oxen stayed right in the middle of the furrow. After we finished plowing, my dad carefully inspected the well-plowed furrows, and in the end he used to tell me, “Good job, look at how straight they are”; whenever I asked him why it was so important, his reply was as simple as it was true, “Because they’re more beautiful this way”. In the simplicity with which my father identified beauty with a straight line, lied the whole meaning of the correspondence between exactness and the successful outcome of any job, from which the concept of beauty arose spontaneously. Isn’t it true, according to the Bible, that after the six days of Creation, God looked at everything he had made and “knew it was beautiful”?

Everyday life, with its normal routine, included a very early breakfast, with toasted bread in the winter, milk and barley coffee. Then we went to work the land and had a second breakfast, for instance bread with vegetables, like peppers; then we had lunch, and I have dreamy memories of my mother and grandmother’s delicious homemade fettuccine. After lunch we had a little rest, that was vital for us, since we woke up at dawn, and which I still view as energizing and enjoyable. Then we went back to work and in the evening, when the sun went down, we had soup and salad for dinner. We ate meat on Sundays.

Illustration by Sunflowerman

All this, every single action, every single gesture, appeared like a ritual and had its own sacred meaning in my eyes. The same routine, day after day over the years, gave each of us strength and certainty for the future. Every year, at Easter, it was tradition to eat lamb, the lamb that we had raised for such purpose. But for us kids, who in the meantime had grown fond of the little animal, it was also a sad moment. We all knew that food is righteous when it is natural and necessary, a belief from which stems the principle of respecting nature, in all its forms. Respecting animals was no different than respecting trees, rivers and all the things of Creation. As sharecroppers, we were custodians of the goods we had been entrusted with, and from this I soon learned that such custodianship is a universal value, encompassing all people as well as the need to respect and keep every single aspect of the place in which we live in order.

Farming life was a reality where every human condition turned into a precious memory for us little ones. Even treasuring the things that happen to us is a value that is often priceless in life. I myself learned this teaching thanks to my paternal grandfather Fiorino’s love, who had a real fondness and esteem for me as a boy.

On Sunday afternoon, my grandfather used to take me to the coffee bar in town to play cards, and I was absolutely thrilled; he dressed up for the occasion: he always wore a clean, bright white shirt with a dark blazer and pants. I was more or less eight or nine years old, and while I was sitting next to him at the card table, I used to count cards and study the moves; on the way home, which was about an hour’s walk, he explained to me the reasons why some moves were good moves and others were bad ones. I cried a lot when he suddenly passed away, due to a stroke at the age of only sixty-eight years. That was my first experience with death and this memory has never left me. It made me understand the dignity that lies in composure when one copes with grief.

The Cucinelli family in 2017. Left to right, Riccardo, Camilla, Penelope, Vittoria, Alessio, Carolina, Federica and Brunello

Grandpa Fiorino loved telling me stories about the war. They were stories about people and, despite the subject matter, sometimes there was even a funny side to them. I recall no mean or cruel episode, just anecdotes that in the end revealed people’s ability to adapt to the toughest conditions, and over time, to even surprisingly remember them with a hint of nostalgia. The one that emerged from his stories was a war without cannons or dead, a war of friendships, even between enemy soldiers. I was very proud of his adventures.

I hold very dear the memory of my aunt Ginetta, who was perhaps the gentlest woman I’ve ever known. She was very religious and she hated committing bad deeds. Her teachings, never a word out of place, were very inspiring to me. Her beautiful son, at the age of six years, suffered from tuberculosis, a tragic diagnosis back then; after months of suffering in hospital he came home, sadly about to die, where my aunt and uncle welcomed him with love. The doctor decided to make a final attempt, but the medicine was only available in a pharmacy that was two hours away by horse. Without hesitation, my father set off and rode until exhaustion, driven by the power of hope. When he came home, he was exhausted; the injection was given immediately and we all waited in anguished expectation, but that same afternoon a very young soul left us. I cannot describe the grief and suffering of the whole family.

Thanks to those memories and stories, inspired by aunt Ginetta’s teachings, I started searching for a connection with the afterworld, and also thanks to this today I have no doubt about the immortality of the soul.

Every beautiful thing I have, I owe to my family and to my rural life, to the ever-changing sky with fleeting clouds, to the infinite light blues, to the starry skies and to the scent of the fields, of manure, of apple tree blossoms, of the dried jasmines that my mother used to put in the wardrobe to make the laundry smell good, and to the authentic flavors of the simple food that I still hold dear in my heart.

Greek philosopher and poet Xenophanes said, “All things come from the Earth”, and I believe I can say we lived in harmony with Creation.

There was more than just the family, however. Life outside of the family, although limited to the school dimension, mattered, because it kept us busy every morning and evening, when I did my homework only thanks to my mother who patiently helped me learn poems by heart.

At school in Castel Rigone, perhaps a bit more harshly than in the family, I had to deal, for the first time, with children who were slightly different from my brothers and I, the villagers. To someone who lives in the city it might not appear sufficiently clear how villagers can look at farmers with a sort of indifference. I made great efforts to look perfect, we always took our muddy boots off before entering the classroom, but nonetheless there was something in the way we dressed, in our hair, inexpertly cut by one of my uncles, in our very accent, which changed ever so slightly just a few kilometers away, that, since the very first day of school, made the other students immediately identify us as farmers, even though they didn’t mistreat us.

When I was fifteen years old my parents, like many other friends of theirs who were farmers, made the difficult decision to move to the city to work in a factory. Here, suddenly everything was new, everything was different, on the one hand we had many comforts, electricity, modern appliances, heaters, the television, the telephone; on the other hand we had lost the boundless sky, the vast fields, the scent of the woods, the smell of animals, the moon shedding its silver light onto the countryside and those enchanting nights spent reflecting and gazing at the infinite starry sky. But, since every moment in life teaches us something, I soon understood that such early technology, those new appliances, were a gift from Creation that could make life easier for us. A healthy gift borne from that same human desire that today is guiding technological evolution toward new progress, such as, for instance, artificial intelligence, a valuable tool that I think will favor the incoming bright future ahead of us.

My father was a factory worker for a manufacturer of reinforced concrete prefabricated elements. When he came home in the evening, I heard him complain about being humiliated by his employers. I saw him disappointed, upset, with teary eyes; he used to wonder, “What have I done to the Lord to be offended like this?”. I was very upset by his unjust suffering; I felt powerless, incapable of defending my father, but deep inside my heart I clearly realized that, although I still didn’t know what life had in store for me, I knew that in the future I would have lived and worked for the respect of moral and economic human dignity. I also learned that anger is anyone's worst enemy. I was always fascinated by Saint Paul’s words, “Do not let the sun go down on your anger”.

Once, however, no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t bring about justice. My schoolmates from the city, or “townies” as we called them, thought we were slightly different from them, and perhaps sometimes their jokes were far from funny. My classmate who sat next to me also came from the countryside; his mother had recently passed away and for a long time the sadness and confusion of his loss made him absent-minded, almost detached from school life. Some older classmates took advantage of his condition and used to steal his morning snack; we didn’t know who the thief was and I didn’t have enough money to buy him another sandwich; how could I stop these not so amiable thefts? One day, I came up with the perfect idea: I asked my mother to make me two bologna sandwiches; I secretly added a good dose of laxative to them, then I put the sandwiches in their usual place and told my friend, “This morning we’ll catch the thief, you’ll see”. About a half hour later, two boys, clearly in urgency, asked for permission to use the restroom. You can guess the rest, but I have to say that they stopped stealing our food, once and for all.

Another great novelty of city life was the typical Italian coffee bar. This place, which was new to me, became the one where I used to spend most of my time. It became my personal university in life and human knowledge. At the time, the patrons were practically all men, of three types basically: construction workers who came after work, students and idlers like me. We used to play cards and joke a lot, but you had to be willing to take them with irony.

At the coffee bar, there was always someone ready to listen to your problems. I happened to be such person, for example, for Lella, a prostitute who, late at night, after work, just like the construction workers, came to the bar looking for comfort. I felt pity for this woman, but at only 18 years of age, I searched for the right words of comfort to say to somebody who’s lived the wrong life, but found none. Confucius said, “It is beautiful to make humaneness one’s home”.

Late at night, words prevailed over card games and discussions started: debate focused on the big topical political issues, then, with great freedom of speech, it moved on to the economy, theology, religion, spirituality, women, jokes.

Some of these students went to classical high school, so they studied philosophy. They talked to me about this discipline that I didn’t know much about, because we didn’t study it at the high school for land survey that I attended at the time. They talked about Schopenhauer, Hegel, Kierkegaard... One evening the conversation touched on Kant. I didn’t understand much of what they were saying but I was immediately drawn to it. I was really curious to know why this thinker was considered one of the greatest philosophers of modern times. The next day, I started looking for more information, and in the end I managed to buy a used copy of one of his major works. I started reading the book, but it was very complicated, especially for me, unused to philosophical jargon. However, his aphorisms and expressions were clear and meaningful! I learned to consider humanity as an end rather than a simple means, and to respect the great harmony that is born between the starry sky above and the moral law within me.

Later on, I grew a passion for many other philosophers, especially from ancient times: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, through the history of Alexander the Great, Seneca, and then Marcus Aurelius, who were advocates of a very humane stoicism, but also Saint Augustine, who was capable of giving philosophic dignity to Christianity, as well as Confucius, Vico, Spinoza, Leibnitz, up to the fathers of the Age of Enlightenment, Locke and Hobbes. How helpful the teachings of these great philosophers – to whom I have dedicated many statues and busts both at home and in the public streets of Solomeo – have been for me.

At the coffee bar, we discussed the matters of life. Ten years of great beauty, even ethical one, where I came to know and learn speed and intuition, patience and harshness, pity and courage. After all the bar, as I mentioned earlier, was my “university in life”.

When I met my beloved Federica I was about 17 years old. She, who today is my wife, was born and lived in Solomeo; to go to school in Perugia she took the same bus as me. I liked her slender figure, her elegance and modesty; it took me a very long time to say even a word to her, because my desire to talk to her, although great, was every time restrained by the fear of appearing too ordinary or of saying something foolish. In the end, I mustered the courage and started courting her but, due to shyness, hers and mine, it wasn’t at all easy. My perseverance in the end was rewarded and after some time we got engaged.

So I started going to Solomeo more and more frequently, hanging out with her friends, and everything there seemed very special to me, despite those places were pretty degraded by the passing of time. Federica’s father owned a little sewing, textile and household shop there, and she would have also opened a small clothes shop one day; I often went shopping with her, and that’s when I started getting intrigued by the world of fashion. By then, I was on the brink of my rebirth.

Federica and I used to talk a lot about the future; I told her about my dream of becoming an engineer, an explorer, a pacifist revolutionary, a humanist... a real mess, that she, who was more reflective than me, helped me resolve and put in perspective. But my positive idealism was unwavering. Time changes things in form but not in substance. From Aristotle to Rousseau, with a gaze encompassing many thousands of years, philosophy has recognized that in human nature there is a tendency towards knowledge, and knowledge coincides with good. If we have a deep understanding of the dreams in our hearts, this is the most important result we can attain in life.'

My Vision of the World

“All things come from the Earth”.

‘This concept by Greek philosopher Xenophanes, in its simplicity, appears immense to me and one of the most apt to express the magnificence of the world.

Almost all the Western philosophers have imagined a universal order in which the meaning of Creation could be recognized; Eastern philosophy, moreover, has imagined reality as an ever-changing flux where all things are in vital tension with each other, and only by recognizing this tension can one live one’s life usefully and pleasantly in harmony with nature.

I have always been attracted by the idea of change. In the 16th century, great humanist Thomas More thus prayed: “God, grant me the courage to change the things I can change, the serenity to accept those I cannot change, and the wisdom to know the difference”. Discernment itself sometimes appears to be the hardest part of change, because it requires knowledge. Acceptance is not always easy when we are confronted with pain: yet Saint Augustine thus prayed: “O Lord, who teachest by sorrow”.

Order and flux, order and change: I see them as two generating sources and I believe that if we can combine them harmoniously we will always be able to pursue fair progress. I like to think that the art of progress is the preservation of order in change and of change in order.

These ideas have guided me, constantly illuminating my way, like guiding lights, torches that have been handed down to us by our fathers and that we will hand down to our children. Isn’t this a great symbol of Time and of its duration? Doesn’t harmony between the past, the present and the future express its highest meaning? Latin poet Lucretius, who is the author of one of the earliest books about Nature, viewed men as runners in life, who pass on the torch to one another, as a symbol of the human thought that is passed on from one age to another, forever.

I like to think of myself, for my part, as a “lamplighter” who continues with passion his mysterious and courageous journey. Today that I have more years behind me than I do ahead of me, I more frequently think that the end of life is the beginning of another life: I learned this from the words that a dear friend of mine told me when my father passed away. And I identify myself in the wisdom of Confucius, who said: “At sixty, I can let my mind wander without transgressing moral law”. We must constantly think about our future life, that of our children and of all those who come after us: the greatest legacy that fathers can pass on to their children is the glory of virtue and of great actions.

I pursue, with faith, the teachings of our fathers, meaning the endless number of great thinkers from the past. My dialogue with them takes place through books, those paper texts whose ancient pages still have the scent of a time long gone and the life of an eternal thought. What a glorious experience is it for us to rediscover these men by drawing directly from their words, posing questions to them and rejoicing in their replies. Books are our teachers and, as such, deserve the utmost care; and so libraries are born, which are temples of human knowledge. How could we forget that knowledge was cultivated for centuries within the protective walls of the Library of Alexandria, founded by the dyadic Ptolemy I, but inspired by Alexander the Great, who had learned its universal importance from the words of his teacher Aristotle?

Every man of wisdom loved books: Emperor Hadrian considered libraries as granaries for the soul; Pliny the Elder thought that the voice of the immortal souls of the departed could be heard in libraries; “Medicine for the soul” was the inscription above the entrance to the library of Egyptian ruler Ozymandias.

I hasten, with moderation and time, to construct, preserve, embellish, and I make great efforts to make things last longer. Preserving is at times neglected, because it requires greater knowledge than constructing, but it’s just as important. I’m convinced, as 19th century art historian and painter John Ruskin advocated, that any object we make retains a part of us and that any product of human labor has its life and its end. We can do nothing more than do our best to delay such end as much as possible, by lovingly cherishing our objects and traditions, by keeping our memory and memories alive. And our memory is the custodian that treasures all things.

If our family, which is a place of peace, lasts, then our home will last, and with it our cities and the whole world, with its immense beauty. Our homeland is the place where we choose to live and where everyone is entitled to stay. But living is not enough, we must live well, taking utmost account, as Kant teaches us, of the starry sky above and of the moral law within us. Furthermore, we must not ignore the human laws that we have given ourselves: my mind goes to Pericles and his magnificent example of democracy in Athens; some laws might not be to our liking, but in their compliance lies our social freedom.

The Siena town hall contains a lovely painting that shows, through the appeal of art, how the Good Government is the one where Wisdom carries Justice, from which Concord is generated. Through an idyllic vision, the artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti illustrates the blessed labor that Wisdom, Justice and Concord guarantee: the painting depicts agricultural labor, the manorial economy where everything served everything else and every laborious man was a craftsman. All of those values are still relevant in today’s world.

Any honest job is good and honorable, and shall remain so. In the 16th century, Benedetto Cotrugli, in his brilliant book, taught us that the job of the merchant is an honorable profession. Craftsmanship is, above all, honorable: what greater gift can we give to the res publica than to teach youth, to educate and bring them closer to the values of craftsmanship? The highest art is the one where a man’s hands, mind and heart are in accord. Isn’t this the meaning of craftsmanship? The latter is, in my opinion, the highest form of humanistic labor, because you learn by practicing it, because it is physically perceivable, because it is the expression of genius, and because it respects natural rhythms, alternating action with rest.

We must alternate work with rest in order to do things well. Progress is natural in work, but we must not forget that there are ups and downs and that it is advisable to accept them both with the same spirit, because we must remember the past, see the present and foresee the future: only thus can we detach and elevate ourselves above physical circumstances. Labor conceived in this way respects human dignity; I’m convinced that healthy labor is pleasing, and that such pleasure perfects the task at hand, and that happiness, among other things, lies in using one’s ingenuity.

I also think that moderation is the most important rule of amiable labor. In other words, fair labor is labor that adjusts its rhythm based on the rhythm of nature, that progresses harmoniously, that brings together desires and plans, fair profit and giving back; fair labor is labor that doesn’t derive from individual decisions, but from dialogue and sharing with others, it’s labor that loves the useful and considers beautiful what is useful to all. Fair labor, today and tomorrow, is labor that recognizes the great value of technology and of artificial intelligence and that avails itself of their results like valuable gifts of the leading human nature.

I believe in a form of contemporary Humanistic Capitalism where fair profit is pursued by trying to cause as little harm as possible to Creation and humanity. I like to think of an inclusive sustainability encompassing material and spiritual values, a real place where the environment, the economy, culture, technology, the spirit and morality coexist, complementing each other in the concept of Human Sustainability.

The glory we gain from labor is pure only when we do not pursue it, but when it pursues us. I like to think that the greatest acknowledgement for the efforts made is not the result in itself, it’s the person we become thanks to these efforts. And it is our moral imperative to grow in knowledge and truth.'

Brunello Cucinelli together with, from left, Josh Hamm, Sharon Stone, and Chris Pine at the event at Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, December 5, 2024.

Recognitions and Awards

Brunello Cucinelli has received a remarkable number of national and international recognitions for his “Humanistic Capitalism” and for his entrepreneurial business:

He was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in “Management, Banking and Commodity Sciences” by “Sapienza” University of Rome, a prestigious title that was meant as a tribute to «the distinctive trait of his entrepreneurial action, which has always been to offer work while fully respecting moral and economic human dignity».

He was chosen by the Association for Industrial Design and the eponymous Foundation as the winner of the Career Award of the XXVII Edition of the Compasso d'Oro. Among the reasons for the recognition, the courage and perseverance with which he "seeks a balance between profit and environmental as well as social responsibility. A vision of Humanistic Capitalism that he has translated into exemplary products and actions, framed in a strategy typical of the best Made in Italy design."

The Department of Architecture of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” awarded Brunello Cucinelli an Honorary Doctorate in “Design for Made in Italy: Identity, Innovation, and Sustainability”, recognizing him as “a perfect ambassador of Italian elegance as a synthesis of culture and heritage, as well as an enlightened and sensitive entrepreneur with exceptional innovative capabilities”.

During the 2025 British Fashion Awards in London, Brunello Cucinelli was presented with the lifetime “Outstanding Achievement Award” for his “exceptional contribution to the world of fashion, as a pioneer who has succeeded in combining luxury and design with a more responsible approach to business”.